Short path distillation is not a new process – but as resources grow increasingly scarce, its relevance is undisputed. UIC has responded to this rising demand by modernising and extending its Process Development Center, which reopened in Alzenau at the end of February. cpp invited Rudolf Opitzer, the company’s Managing Director, to shed light on the background to this latest trend.

UIC Process Development Center gets fit for the future

New products from old raw materials

Short path distillation is not a new process – but as resources grow increasingly scarce, its relevance is undisputed. UIC has responded to this rising demand by modernising and extending its Process Development Center, which reopened in Alzenau at the end of February. cpp invited Rudolf Opitzer, the company’s Managing Director, to shed light on the background to this latest trend.

UIC claims to be a pioneer of short path distillation with more than six decades of experience in the field, yet you’ve only just celebrated your twenty-fifth anniversary. How can that be so?

Opitzer: Short path distillation was invented by Leybold of Cologne in the fifties of the last century. When Leybold was sold, the technology passed to Heraeus, where it fitted very well into the vacuum engineering portfolio. Nevertheless, business failed to develop satisfactorily under the umbrella of such a large corporation. As a result of this, Heraeus resold the division twenty-six years ago now to UIC Inc., an American firm that manufactures instruments, though without any significant improvement. The turning point was the MBO a good twenty-five years ago, when Norbert Kukla and his colleagues took over UIC and put it back on track. And it was the then management which helped short path distillation become the success story it is today. Eight years ago, the company was acquired by BDI, BioEnergy International. BDI builds biodiesel facilities, where short path distillation is a strategically important component. We’ve belonged to the BDI Group ever since and we’ve benefited in plenty of ways.

What might they be?

Opitzer: BDI is financially strong. That means we can be more relaxed about tackling major projects. On top of that, they’re a very innovative company that put us under permanent pressure to innovate, too.

And what about the drawbacks? Aren’t you heavily dependent on BDI?

Opitzer: Yes, but only as far as the biodiesel segment is concerned. We supply to eight different industries in total and biodiesel is just one of them. We’re also extremely active in pharmaceuticals, food processing, fine chemistry and polymers. Fish oil is another key sector, notably omega-3 fatty acids. And in the last few years, there’s also been a boom in recycling.

How is life treating the company today?

Opitzer: Our sales are in the region of ten million euros and our payroll has increased from 35 to 45 in the last eighteen months. We’re fast developing into a systems engineering specialist for large-scale facilities, and so far we’re very successful. As regards market potential, 90 % of our systems are currently exported, though that figure varies somewhat depending on individual orders. When you consider that sales, which are directly linked to incoming orders, amount to ten million euros, a single order that’s worth a million makes a big difference.

That takes us to your product portfolio. Could you maybe give us a brief rundown?

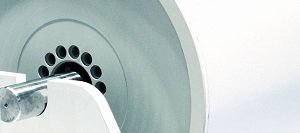

Opitzer: Short path distillation and thin film evaporation are the two mainstays of our business. With short path distillation, the condenser is inside the apparatus while with thin film evaporation it’s outside. If the condenser is built in, the path of the vapour phase is short and there’s only little pressure loss, meaning that lower pressures can be achieved (from 0.001 to 1 mbar). Thin film evaporators work with higher pressures between 1 and 100 mbar. Starting from these core components we manufacture complete systems ranging from laboratory plants in glass through pilot plants (which are similar in size but made of stainless steel) to large-scale, all-stainless steel industrial plants up to 40 m high.

Which substances do you mainly use?

Opitzer: Vacuum distillation is a niche market in which we’ve become specialised. It’s used for substances containing temperature-sensitive components or having a high boiling point, which would evaporate at 400 °C under normal pressure. Polyurethanes and waxes are typical examples of products that can be purified in this way, for instance, owing to their high boiling point. Palm oil, fish oil, vitamins and pharmaceutical intermediates are just some of the temperature-sensitive substances we process.

And what services do you provide in this case?

Opitzer: Our services begin with customer trials in the Process Development Center. Ideally, the customer comes to us with a problem to solve. One of our clients recently approached us with a waste product, looking for a way to extract valuable substances. “How to” challenges are the kind we like, though of course only if we can achieve the separation through distillation. We map out the separation parameters and develop the process together with the customer. Our job is to determine the degree of purity with which the product can be recovered, the feed rates the system can handle and the yield that can be realised. This information is our starting point whenever we design a large-scale plant. We often submit a budget quotation at this stage, to enable the customer to work out a financing or business model. We also produce small quantities of the material, however, for instance as samples for the customer‘s customers. We then build the plant, deliver it and commission it. Remote support, spare parts, servicing and modifications are all integrated in an after sales package.

Does that also apply to older systems where a retrofit is required?

Opitzer: That’s a situation we actually encounter very often. Let me give you an example: a customer of ours was still using a system that was built way back in 1965, in the Leybold days, for mineral oil products. Unfortunately, the quality was no longer up to scratch and the throughput was also sub-optimal. We conducted trials with the samples that were supplied to us and found that both the quality and the system capacity could be significantly improved with no more than a few simple tricks. In some areas, the customer was able to continue using the old systems while in others, new process stages were unavoidable.

What exactly does this customer do? Treat mineral oils?

Opitzer: Mineral oils are not only refined; this customer also uses them as a raw material from which individual fractions such as glycerines are extracted. After all, mineral oils are a starting product for anything to do with polymer chemistry and they’re far too good for burning.

You completed a major extension of your Process Development Center last year. How much did you invest in it?

Opitzer: We invested over a million euros in cash and a lot more than that in nerves. It’s a surprisingly high sum because we didn’t make very many changes to the apparatus.

So what was it that cost all that money?

Opitzer: That’s easy to explain. Picture our Process Development Center as a huge toolkit. Our main components represent the foundation: short path distillators, thin film and falling film evaporators, degassers and rectification columns. We combine these various components as required by the individual trials. None of them have been changed; what’s new are the frames in which the systems are mounted. Thanks to the new assembly system, we can now reconfigure them much faster. It’s a highly standardised system, which means the components are also interchangeable from one system to another. The safety technology was radically improved at the same time. That was a second very relevant aspect. More and more of the substances we process today are potentially hazardous to human health. The ambient air needs to be monitored and powerful, directed exhaust apparatus is a must. Our systems are now completely enclosed because of this. The gases can no longer spread throughout the room and the air flow through the systems is directed. Waste air is exhausted either upwards or, if the gases are heavier than air, downwards. A further factor influencing costs is that our projects have a far higher frequency than before and the capacity of our Process Development Center has been doubled. In the past, we were forced to use systems belonging to our research and development department for customer trials. The system we have now was built as a completely new, standalone solution, so that our in-house R&D team can literally work 365 days a year regardless of any trials that are taking place.

Was the original R&D system moved to the new Process Development Center?

Opitzer: No, we’ve got a separate area today for research and development. And in the Process Development Center we can conduct trials for two different customers at once in two fully equipped rooms. That’s something else that’s decisive because most of our projects are strictly confidential. That’s why there are now two separate entrances and a proper data recording concept. The third key innovation is the totally new control system. It lets us record data on an industrial scale and our customers see the same evaluation as they do later when their large-size plant is up and running. The control technology and user friendly data preparation are identical. We can run every system, and monitor and evaluate the data it measures, from any workstation via the network.

What system do you use?

Opitzer: A Siemens S7 – it’s the industry standard. And our customers like it because they see what they get.

Could you describe one of the projects to us that’s currently on the go in your Process Development Center?

Opitzer: The source material for the project is palm oil. Free fatty acids are separated from the oil: lauric acid and a triglyceride with antibacterial properties for the pharmaceutical industry – you could say it’s a biological antibiotic. After separating the aroma components as well, it can be used for cosmetics. The product thickens and is an ideal additive in creams and gels. Lauric acid extends a cream’s shelf life and has an antibacterial effect. That’s one typical application. The customer comes to us with a raw material, in this case a viscous yellow mass. We turn it into a clear product. It’s a classic example of vacuum distillation. If the temperature is too high, the organic substances are denatured. The residence time with short path distillation is one minute; the product is only exposed to a temperature of 120 °C very briefly and then cooled down again straight away.

How do you approach a project of this kind?

Opitzer: Projects like this are becoming a regular occurrence. That’s why we decided to develop our Custom Advanced Technology (CAT), which maps the whole process from the original idea through the R&D and the Process Development Center to the final production plant. More and more customers come to us with raw materials, for example from sidestreams, that in the past have been disposed of as waste even though they contain valuable substances. The customer could know of, say, three or four pharmaceutical companies that are interested in these recyclable materials. We design a process in collaboration and take care of all the R&D, especially the research work. Has a patent already been granted? What experiences are described in the literature? We conduct trials on a micro-scale and cooperate with institutes or universities. If this preparatory work goes well, the project is passed to our Process Development Center, which records the large-scale parameters to enable us to actually build the system.

What present trends have you noted and where, in your opinion, do the future markets for short path distillation lie?

Opitzer: The most important trend, in a nutshell, is “new products from old raw materials”. We isolate tocopherol and vitamin E from palm oil, remove POPs from fish oil and then extract omega-3 fatty acids. However, we also investigate alternative sources such as algae and we process waste oils and brake fluids. In the future, it could even be a viable proposition to squeeze out more bituminous residues in view of the rising prices for end products.

www.cpp-net.com search: cpp0216uic

“Mineral oils are valuableraw materials and they’re far too good for burning”

Angelika Stoll

Angelika Stoll

Editor,cpp chemical plants & processes

Share: